Welcome back to the Short Fiction Spotlight, a weekly column co-curated by myself and the venerable Lee Mandelo, and dedicated to doing exactly what it says in the header: shining a light on the some of the best and most relevant fiction of the aforementioned form.

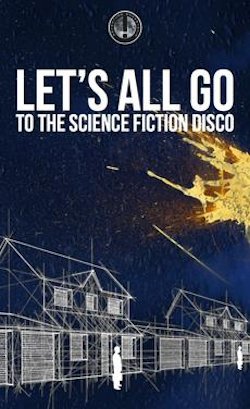

Today, we’ve all been invited to the science fiction disco by the inaugural volume of Adventure Rocketship, a moreish new magazine masterminded by prolific critic Jonathan Wright to celebrate genre-oriented essays and short stories both.

We’ll look at two of the latter tales today, namely “Starmen” by Liz Williams and “Between the Notes” by World Fantasy Award winner Lavie Tidhar, but you can find out more about the fascinating first issue here, and place your orders accordingly.

The retro setlist starts with “Starmen” by Liz Williams, a sad, sweet and ultimately soaring story about a boy’s discovery of David Bowie. Forty years later, our narrator recalls how his youth moved to the sweeping beat of the titular tune; how lacklustre his life was before he glimpsed this formative figure on Top of the Pops, and how very vibrant it became afterwards.

Williams illustrates this coming of age tale wonderfully, by considering colour at every stage. At the outset her palette is patently plain, but her protagonist rapidly becomes enraptured by a door painted purple, striking in an otherwise samey neighbourhood:

Apart from that magnificent blazing occult door, it was all grey—grey sky, grey buildings, grey ponderous river Thames winding through the city, and when I was a little kid, I always wondered if someone had stolen all the colour out of the world, or whether there was just something wrong with my eyes. I mentioned it to my dad once—I didn’t want to worry my mum, who was ill by then—and he just gave me a funny look and said there was nowt wrong with my eyes and to stop making a fuss. So I did.

This quote touches on a number of the narrative’s other aspects, because in addition to being a love letter to the transformative qualities of beautiful music, and a subtle study of the struggle some individuals have relating to others, “Starmen” showcases a father and a son coming to terms with an absence in their family:

She died when I was nine, and it’s always bothered me, why I didn’t feel it more. Dad did, I know. Used to hear him crying into a hankie, late at night when he thought no one could hear. He’s a proud man—you’re not supposed to have feelings north of the Watford Gap, for all we live in London now. But he does, and I don’t, and I don’t know why. Never have had, really. It’s always been like looking at the world through a pane of glass and dirty glass at that, as if I didn’t understand what was going on.

“Starmen” has all the trappings of an upsetting story, but instead, it’s revelatory, positively celebratory, because when Williams’ protagonist encounters the man of the moment—the man who fell to Earth a little later—everything about the fiction seems to shift; its tone, its tint, and its central character are all uplifted. Indeed, hearing Starman leads said to see the world in a bright new light:

Outside, the rain had blown through, leaving a brightness behind it, and I went out of the door and down the road to the park. Very tidy, the park, with manicured grass and a bandstand and the kind of trees that little kids draw, like green circles. I thought the park was a bit boring, but today it had a kind of newness about it, as though the rain had left it cleaner, and I walked through it in a daze, with the song running through my head. I looked up into the trees at the blare of the sky and thought of a blue guitar.

Liz Williams paves the way for this change wonderfully, grounding the earlier section of her short in a world utterly without wonder. Thus, though “Starmen” isn’t actually science fiction in any measureable sense, baby Bowie’s effect on the boy whose experience this very personal piece revolves around is effectively out of this world.

It’s a lovely, understated short; a Technicolor love letter to a man who moved many, and the music with which he made that magic happen.

“Between the Notes” by Lavie Tidhar is darker than “Starmen” by far, but it’s also a rather romantic narrative, albeit after a fashion. Our protagonist in this instance is a time-travelling serial killer who rubs shoulders with Jack the Ripper—another chronologically displaced person, as it happens, hence his disappearance from the period in which his name was made:

The truth was he surfaced again in 1666 during the Great Plague, killed at least seven other victims that we know of, started the Great Fire of London to cover his tracks, and time-jumped again, to 2325, where he was at last apprehended, but not before three more victims died.

I still see Jack from time to time. There’s a place, and a time.

In any case, our narrator—another nameless creation, though there is reason to believe Tidhar is in a sense writing about himself (more on which in a moment)—our narrator is at pains to differentiate himself from the likes of John Wayne Gacy and the Boston Strangler: “I’m not like the other guys,” he advises. “They kill to satisfy some inner desperation, some terrible void. Not me. I do it out of love.”

Needless to say, given the venue in which “Between the Notes” appears, it’s a love of music that moves this man to murder, and so we watch him immortalise Mozart, kill Kurt, and eliminate Lennon, all with a certain deference. Because “musicians, like writers, fade out young. They are spent quickly, like bullets. To die young is to live forever. To die old is to be a legend diminished, a shadow-self,” thus our cut-throat does what he feels he must, the better to preserve these icons of song.

He may be a cold-blooded killer from the future, but Tidhar—ever the canny craftsman—manages to make his central character relatable by interspersing markedly more personal reflections amongst the infamous episodes aforementioned. Little by little, we come to grasp what led him down this dark path, namely his adoration of Inbal Perlmuter, the lead singer of a ground-breaking Israeli rock band, who died before her time.

The only element of “Between the Notes” that left me cold was Tidhar’s decision to qualify these sections of his short as “real.” All others, accordingly, are “made up,” and whilst this adds especial significance to the Perlmuter parts, I’m sure the author could have achieved this without essentially dismissing a great swathe of the fiction. Otherwise, “Between the Notes” is a beauty. The prose has poise; and the narrative, though initially disparate, coheres meaningfully come the rueful conclusion.

I’m going to leave you today with one last quote from Tidhar’s tale, which I think speaks powerfully to the appeal of this story—this entire magazine, even. It touches on the power of music to transport as well as transform its listeners, and that’s a sentiment even I can get behind:

You know how you can listen to a song and it evokes, suddenly and without warning, a moment in the past, so vividly and immediately that it stops your breath? That summer you first fell in love, the music playing on your grandfather’s old radio in his house, before he died, the song playing in the background in the car when you looked out of the window andsuddenly realised you were mortal, that you, too, were going to die. The song they played when you were a child and lying in your cot and there was a hush in the room and outside, through the glass, you could see the night sky, and the stars, so many stars, and it filled you with wonder. All of those tiny moments of our lives, filled with half-heard music.

“Close your eyes. Listen to the notes. Slow your heart beat. Time stretches, each moment between notes grows longer, longer… time stops. Listen to the silences between the notes.

“Nothing around you. The world fades. You stare into the darkness there, that profound silence. A chasm filled with stars. If you could only slip between the notes then you can go anywhere, and you could…”

Niall Alexander is an erstwhile English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com, where he contributes a weekly column concerned with news and new releases in the UK called the British Genre Fiction Focus, and co-curates the Short Fiction Spotlight. On rare occasion he’s been seen to tweet, twoo.